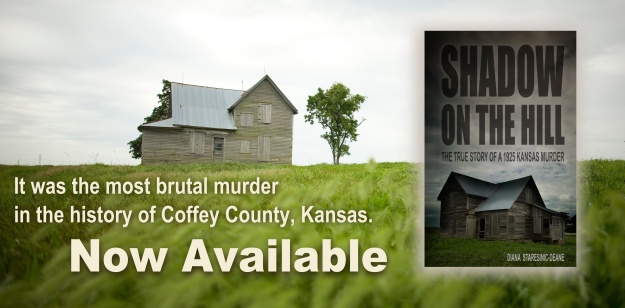

It was the most brutal murder in Coffey County, Kansas’ history.

On Decoration Day in 1925, John Knoblock returned to his Kansas farm to find his wife slaughtered on the kitchen floor. Within hours, dozens of lawmen, family members, well-meaning neighbors and gawkers paraded through the Knoblock farmstead, contaminating and destroying what little evidence was left behind. A small team of inexperienced lawmen, including a newly elected sheriff who had never run a murder investigation, attempted to reconstruct and solve the most gruesome murder in the history of Coffey County, Kansas.

What begins as the murder of a very private and somewhat sickly farmwife and mother turned into a multi-county fiasco. Two different pairs of bloodhounds were called in and pulled investigators in two different directions. Florence Knoblock’s family disobeyed the sheriff’s orders and scrubbed clean the crime scene before the investigation was complete. Fingers began to point in so many directions, neighbors saw everyone else as a potential suspect. In a county where many residents didn’t have locks to latch at night, women began to keep shotguns by their stoves to point at anyone who knocked on their doors.

The investigation stayed on the front page of several local newspapers for nearly a year. Two of Kansas’ most prominent reporters, William Lindsay White at the Emporia Gazette and John Redmond at the Burlington Republican, brought the story to life through colorful commentary and excruciating detail, amassing hundreds of pages of clippings between the first article announcing the murder and the last article announcing the outcome of the trial.

Before there could be a trial, however, the law had to find a suspect. Four different men were arrested. Sherman Stevens, an African American construction worker who helped build the bridge at the intersection near the Knoblock farm, was the first to be arrested, and languished in the county jail for weeks until he was finally cleared and released. Two other passersby were arrested and released. The young county attorney finally set his sights on the widower, John Knoblock.

An awkward man, John Knoblock was known for his nervous ticks and twitches and uncomfortable demeanor. He was a somewhat simple homebody who preferred to stick close to family. With no better suspects and the public’s demand to hold someone accountable, the prosecution arrested and charged John Knoblock, a decision that would tear the community apart. His friends and family, including his late wife’s parents, were so confident in John Knoblock’s innocence that they mortgaged their farms to raise the $25,000 bond.

Many who didn’t know him were just as sure of his guilt.

More than 100 people were subpoenaed for the biggest trial ever held in the courtrooms of Coffey County. Even as the trial generated excitement in the community, it was clear that there were problems with the prosecution’s case. Several key witnesses, including the coroner, vanished without a trace. Evidence that was to be presented at the trial disappeared. It would be revealed that the most important witness the prosecution presented—the man who claimed to know John Knoblock was having affairs with his wife’s sisters—admitted on the stand that the prosecution paid him for his testimony.

Hundreds of citizens packed the courthouse or stood on the courthouse lawn to listen to the courthouse proceedings. Reporters from around the state followed the trial from sunup to sundown, filling the pages of their hometown papers with notes from the trial.

After 18 votes, the county’s most expensive trial ended in a hung jury.

Roger Knoblock sat with his father throughout most of the trial. Journalists reported that he wiped away his father’s tears as the prosecution accused John Knoblock of murder.

Undeterred, the prosecution pushed for a retrial. Realizing Knoblock could not get a fair trial in Coffey County, the trial was moved to Emporia, the Lyon County seat, where citizens treated the trial like a sporting event. Far different from the somber and sensational air of the first trial, the Emporia trial was peppered with humorous and frustrating interruptions ranging from loud trains and backfiring cars that drowned out testimony to the judge’s admonishments of a misbehaving audience.

In less than six hours, the jury acquitted John Knoblock, who left Emporia a shattered, homeless, jobless man others would be suspicious of for the rest of his life.

An old story reemerges.

I’d never even heard of Florence Knoblock until her story fell at my feet.

One hot August morning in 2007, I was chasing after a group of hyper children playing hide-and-seek in the stacks at Emporia Public Library, in Emporia, Kansas, where I worked as a library assistant. As I was passing through the stacks between the non-fiction collection and the genealogy area, a folder slipped off of the shelf and fell at my feet. It was thin, made with heavy green paper embossed in a faux leather pattern . Someone had scrawled “Knoblock Murder” in a shaky hand within the boundaries of the little rectangle on the cover.

The brads inside held nothing, but the right pocket contained several news clippings. “May Have Murderer,” read the first Emporia Gazette headline. I turned the clipping sideways and saw “2 Jun 1925” written in the same old-style cursive as on the folder cover.

Intrigued, I carried the folder back to the reference desk to read. I shuffled through the microfilm printouts. Twenty-two newspaper clippings from two different newspapers – the Emporia Gazette and The Olpe Optimist, which had served the small town of Olpe, nine miles south of Emporia.

The headlines were sensational, in bold capital letters across the width of their respective newspapers: MAY HAVE MURDERER: BURLINGTON AWAITS REPORT ON FINGERPRINTS. CALL IN DETECTIVES: KNOBLOCK MURDER PROBE WILL BE PUSHED. MYSTERY IS GROWING: NEW DEVELOPMENTS TEND TO CLEAR NEGRO. CALL OUT A POSSE: BURLINGTON THOUGHT MURDERER WAS CAPTURED, NIGHT RIDE ONLY TO FIND WEARY PEDESTRIAN.

That morning was slow enough that I was able to read a couple of paragraphs here and there between patrons needing assistance. It was In Cold Blood meets the Keystone Cops. Absolute tragedy marred by klutziness and moments of humor. It was real life.

It was also gruesome. John Knoblock and his four-year-old son, Roger, returned to the farmhouse after a trip to town to discover the body of Florence Knoblock in a pool of her own blood on the kitchen floor. Florence’s skull was crushed, her head having been beaten repeatedly with an iron lid from the woodburning stove, and her throat had been slashed to the bone with a shaving razor. Twice. Four different men were arrested. Florence’s husband was arrested twice, and then tried twice in two of the most sensational trials in Kansas. I flipped to the last newspaper clipping in the folder. It was dated November 25, 1957. It was John Knoblock’s obituary.

Florence Knoblock’s murder changed everything—for her family, for her community. I had to know how the story ended. I had to understand why a tight-knit farm community—people who worked together, worshipped together, raised their children together—would ultimately choose to believe they had identified but failed to convict a murderer rather than accept the possibility that the real murderer lived and worked among them in anonymity.

I spent the next few years searching for the truth. I visited small towns, interviewed people who remembered the trial first hand and descendants who heard the stories. I dug through courthouse records and newspaper clippings. I looked inside the murder site – an old farmhouse that stands empty in a pasture – and retraced the steps of the bloodhounds and the contradictory steps of the investigators.

I believe I found answers that, while perhaps not identifying the killer, at least exonerate John Knoblock.

Shadow on the Hill: The book project

Shadow on the Hill: The book project

Florence Knoblock’s murder impacted communities both near and far. The story is an important part of 1920s Kansas history, a snapshot of life and crime an era when the old was giving way to the modern. Thanks to the many supporters who promoted and helped fund this project, Shadow on the Hill is now available in paperback and eBook formats.

The house where Florence Knoblock was murdered still stands in a pasture in Coffey County, Kansas. Photo by Stephan Anderson-Story.

I know this family. They have the pictures you have of the family of all the girls and the one little boy named John

I am amazed at how many times I have had someone approach me (when hearing about this project) to tell me the know someone connected to the family. The Mozingo and Knoblock families are spread far and wide!

This is a sad and fascinating story! I’ll forward the link to my reading group.

Thank you, Laurie! I will keep everyone appraised of the release date. Right now, the goal is spring 2013.

Did you come across the murder of the Reed woman around the Gridley area in 1926. Her husband was unsuccessful in cutting her head off with a razor. They described her body laying the same way as Knoblock’s. They do know for a fact the husband killed her.

I’m always amazed when people look back nostalgically at earlier times and talk as if all of the violence and crimes against others were invented with the advent of television. Some of those crimes were just gruesome and incredibly personal. I would like to read more about the Reed story. I’ll have to see if I can find anything on it through my NewspaperArchive account.

I just researched this tonight and I guess she’s my great great aunt (Florence Knoblock/Mozingo). I can’t wait to read this book when it gets published. Keep up the good work!

Thanks for posting, Sydne! If you aren’t already following it, let me point you to the facebook page that is followed by several people in the Knoblock/Mozingo family, many of whom are genealogists. http://facebook.com/florenceknoblockbook There are photos and newspaper headlines and documents there, too.

For obvious reasons, this story fascinates me. I look forward to reading it.

Shirl Knobloch

Author, Reiki Master/Intuitive Counselor

I have nominated you for the Dragon’s Loyalty Award. You can find the rules/guidelines here: http://whenibecameanauthor.wordpress.com/2013/03/22/dragons-loyalty-award/ Great job and hope you enjoy it!

Hi Diana. Loved the book. It must have taken a lot of research, not to mention the difficulty with people not being ‘with us’ any longer. You’ve done a great job & had me through the whole book. Thanks. BW

Thanks so much! I can’t take much credit for the story, but it’s nice to hear that readers liked the writing, too!

As you can see, my maiden name is Knoblock. I was born in Leroy, Kansas and lived there until I was 10. Until I accidentally came across your book, I had never heard this story. I am interested to know if John Knoblock had siblings, and if so, their names.

Sherry, thanks for your post! There were lots of Knoblocks in Coffey County at one point. According to the obituary of Charles Knoblock, who was John Knoblock’s father, Charles had at least a brother (John) and a sister (Hattie). Charles himself had three sons: Frank (who moved to Virginia), John (who ultimately moved to California), and Charles (who also moved to California). John’s uncle John stayed in Burlington. This means there were a lot of cousins who were in the area at one time or another, and because many of them share names, it can be a bit confusing to sort out. The Coffey County Museum has a genealogy on the Knoblocks in their research room, and if you’re in the area, you might want to take a look to see where you fit in on the family tree. There is at least one error–the genealogy makes no mention of John Knoblock’s second wife, instead skipping on to wife number three–but there are lots of family photographs and other information you might find interesting and helpful.

I’m a Knoblock and had never heard this story!!!

You are not the first Knoblock to have told me this. I think the family really wanted to move on after this trial was over, and they just didn’t talk about it.