It doesn’t matter if you’re a historian, a genealogist, or an armchair history buff: when it comes to digging into your own family’s history, all researchers eventually slam headfirst into the Wall of Family Silence.

The Wall of Family Silence is that almost impenetrable barrier our own family members put up when we start asking questions about the experiences of our own people. And that wall–as formidable as any concreted, razor-wired, electrified barrier–will shut you down when you ask questions.

“I really don’t want to talk about it.”

“Oh, there’s really nothing to tell. My life isn’t that interesting.”

“It’s not your business.”

“I don’t remember.”

The Wall of Family Silence.

Years ago, a professor acquaintance and I were discussing the challenges of gathering family stories from immigrant family members.

“I just don’t know much about what life was like for my grandparents or great-grandparents,” I remember saying.

“You have to remember,” this acquaintance said, “that most of our immigrant ancestors didn’t give up everything they had because life was good and they were happy. Some of those memories are hard to talk about.”

The Wall of Family Silence.

Fast forward to 15 years later, when I am working in a local history museum and we’re developing an exhibit on World War I.

Our museum’s exhibit featured real helmets and uniforms visitors could try on. That steel helmet is even heavier than it looks.

I was visiting my maternal grandparents while this exhibit was going up, and I was telling them about how small the uniforms were, and how we learned many men from our county were rejected from service because they were malnourished.

Now, my grandparents weren’t old enough to experience the Great War. But they were around for the drawn-out aftermath and World War II, and they were experiencing it from present-day Croatia.

I was telling them about all of this to pass the time, to tell them about what I’m doing. But what I didn’t know is that telling them about my experience with the World War I exhibit was like leaning a ladder over the Wall of Family Silence.

My grandparents began to tell me stories about what it was like for them to grow up in a country in the middle of the mess. They told me about how it impacted their education, their opportunities, and the potential dangers. They told me about my paternal grandmother’s husband, who was tortured to death.

They told me a lot of things I had never heard before.

They never saw the exhibit. But my talking about the hard things our local people experienced during World War I was like giving my grandparents permission to talk about the hard things they experienced before and during World War II.

This summer, we installed an exhibit on the Home Front experience during World War II. I was telling my dad about it over dinner one evening.

“There was a POW camp in Ottawa,” I said. “A lot of those guys worked on farms and built good relationships with people in Franklin County.”

“My grandfather was a POW during World War I,” my dad said. “He and my uncle and a bunch of guys from our village were there with Tito. But Tito was just another guy back then, not the president of Yugoslavia.”

Another rope tossed over the Wall of Family Silence.

The ordinary and extraordinary experiences of our ancestors shaped the people who shaped us. All of our families have stories to tell. Some of those stories are hard to tell, and some of those memories are buried deep. Sometimes it’s hard to get family members to open up about their lives.

And that’s where a museum or historic site can be a magical place. Artifacts, photographs, exhibits, buildings–they stir memories. They acknowledge those personal stories are important. They create context.

They offer a safe conduit for a parent or grandparent or aunt or uncle to say,

“I remember this.”

“When I was a little kid…”

“This happened to me, too.”

“My grandmother once told me about the time when…”

“Did you know that when your dad was a little boy, he…”

Any museum might have an artifact or exhibit that will create a spontaneous account of family history. There are also many Kansas museums that delve into tougher topics. Here are a few to consider:

Miners Hall Museum, Franklin, Kansas

This museum focuses on the history of coal mining, immigrant families, and the rights of laborers. I visited a few years ago and even though my own family never lived in southeast Kansas, I could see elements of my family in their stories.

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, Topeka, Kansas

When you walk in the front doors, you’ll see a sign that says, “Where Hard Conversations Happen.” This site looks at both the history of school desegregation and the fight for equality. I keep trying to blog about my experiences there, but I realize I’m still processing my visit, which was emotional and inspiring.

Strawberry Hill Museum, Kansas City, Kansas

Housed in a former church-run orphanage, this museum explores the history of the orphanage (created to care for children orphaned during the 1918 flu epidemic) and the history of the immigrant communities in the Kansas City area.

POW Camp Concordia Museum, Concordia, Kansas

Once a POW camp for German prisoners captured during WWII, this camp is an opportunity to understand a different side of the war experience. It’s on my list of places to visit.

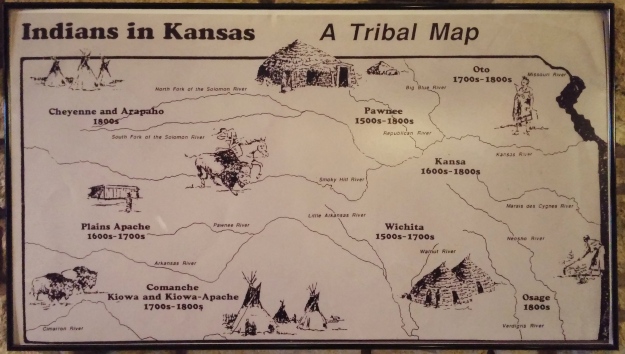

Pawnee Indian Museum, Republic County, Kansas

This museum offers the story of the lives of the Pawnee. It’s an opportunity to learn how the Pawnee lived and how settlers of European descent altered their futures. It is one of my favorite Kansas museums.

Share your story! What museum or historic site experiences inspired your family members to share personal history?