When I was researching the Knoblock murder, I really struggled to understand why the citizens of of Coffey County were so quick to arrest Sherman “Blackie” Stevens and continue to keep him in jail despite having verified his alibi and likely innocence. As modern readers, we need to take a step back and look at race relations in Kansas in the 1920s to better understand what was happening in Coffey County and the potential danger Blackie Stevens was facing.

Kansas and the KKK

It is a common misconception that the Ku Klux Klan rose to power immediately following the Civil War and continued to gain momentum through the 1930s. The popularity the the KKK declined steadily through the 1870s, only to experience a resurgence in membership and power in the 1910s and 1920s. The KKK, which began as a Southern institution, worked its way into Kansas social circles through the early twentieth century and by 1925, Klan supporters controlled the Kansas Senate and had a good grip on the seats in the Kansas House of Representatives. This was scary news for minorities, immigrants, Catholics, and anyone else of whom the Klan did not approve.

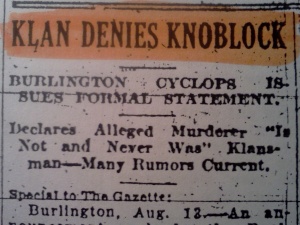

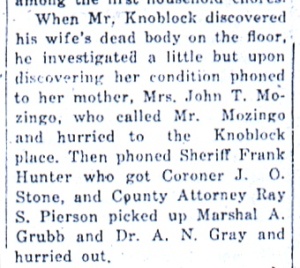

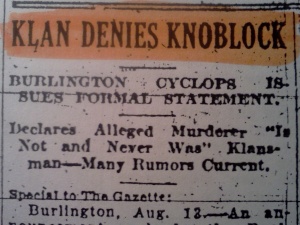

Thanks to the newspapers, we know that the Ku Klux Klan was operating in both Coffey and Lyon counties in 1925 and 1926. In fact, the KKK publicly denounced any connection to John Knoblock about the time that he was first arrested for the murder of his wife. Rumors were circulating that his arrest was delayed because of the KKK’s influence. According to the Emporia Gazette article, “…whether or not Knoblock ever was a klansman, it is certain that he is one no longer…as the leaders of the order have been embarrassed by stories connecting his name with the organization.”

Not wanting to be associated with the murder of Florence Knoblock in any way, the normally invisible KKK publicly denies any association with John Knoblock.

Meanwhile, in the Daily Republican, we occasionally run into ads not unlike ones for other fraternal organizations.

This ad appeared in the May 15, 1926 Daily Republican.

Not everyone was a fan of the KKK. William Allen White, the editor of the Emporia Gazette, was adamantly opposed to the Klan and ran for governor primarily to draw attention to the problems the KKK brought to Kansas. Charles Griffith, the attorney general who took an interest in the Knoblock murder case, was also working to drive the Klan out of Kansas.

In June of 1926, the Emporia Gazette records an ongoing battle with the Klan, which wanted to march in a parade in downtown Emporia. The attorney general’s office issued an order disallowing the Klan to march with their masks in place, and the Klan argued that it was a violation of their rights to impose such an order.

It took a legality to finally push back the tide of the Klan in Kansas: they did not have a charter to operate in the state. After the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the Klan’s appeal, they were forced to cease business in the Kansas. By this time, members around the country were reconsidering their associations with the KKK, and the Klan began to rapidly decline in numbers and influence.

Lynching and Law Enforcement

Lynch mobs did happen in Kansas, even if it wasn’t as frequent as in other states. The UMKC School of Law suggests there were 54 reported lynchings between 1882 and 1968, which is a low number when compared to Georgia, where 531 people were lynched in the same time period. Kansans were also more likely to lynch regardless of race; of the 54, 19 were African American (compared to 492 of the 531 lynched in Georgia).

Still, lynchings were regularly reported, even if they happened in other states. At the time of the Knoblock murder investigation and trial, stories about lynchings appeared in the newspaper.

Reports of a lynching in the August 7, 1926 Emporia Gazette.

Does this mean that Sherman Stevens was in real danger?

The potential for danger was real enough.

Today, we would immediately argue that the sheriff violated Sherman Stevens’ rights by holding the man in prison for several weeks despite the fact that no charges were brought against the man and even the newspapers announced that evidence appears to clear the Sherman Stevens of any guilt beyond having worked on a bridge close to the Knoblock home and accepting strawberries from Florence on a previous occasion. Yet, we have to look at what else was going on in Kansas at the same time.

Rumors were circulating in surrounding communities about the supposed mob that was going to lynch Sherman Stevens. Though he refutes the seriousness of these rumors, in the June 5, 1925 article “Some Wierd [sic] Tales Being Circulated About Burlington,” John Redmond writes, “There was some talk of lynching the negro suspect, but half of those who talked it wore a silly grin as they said it. One loud-mouthed man might have turned that crowd into a mob, but there was no leader and consequently nothing that looked like a mob, but the officers were taking no chances and kept the negro away as a precaution…”

The talk was there. The situation didn’t escalate because there wasn’t an instigator.

To the poor, inexperienced sheriff’s credit, all indications show that the law truly did investigate Sherman Stevens’ whereabouts. I really believe that they would have released Sherman Stevens much sooner if they were able to redirect the public’s attention to another, more viable suspect. However, because there was no other suspect, they continued to hold Sherman Stevens in jail for his own safety until speculation turned to John Knoblock as the potential murderer.

What happened to Sherman Stevens after his release remains a mystery. We know that he spent some time in Garnett, Kansas, because he had communicated with the sheriff. But soon after, he leaves Anderson County and is never heard from again.

Disturbing to me is the fact that, in an interview with John and Florence Knoblock’s granddaughter, I was told that she and her sister grew up believing that their grandmother’s killer had been hanged.

Did a secret lynch mob chase down Sherman Stevens? Though we don’t know definitively, there is no evidence to suggest that he was lynched. I can’t imagine that the community would have allowed John Knoblock to endure two trials if they believed strongly enough that Sherman Stevens was the real killer.

Additional Reading

Kansas Battles the Invisible Empire: The Legal Ouster of the KKK from Kansas 1922-1927 by Charles William Sloan, Jr. Kansas Historical Quarterly, Autumn 1974.

History of Lynchings in Kansas by Genevieve Yost. Kansas Historical Quarterly, May 1933.