During the two years I spent researching the story of Florence Knoblock’s murder and the subsequent investigation and criminal trials, I was astonished by the number of names I encountered. I expected to find details about Florence and her family, but I hadn’t really appreciated just how well I would get to know the people living in Pleasant Township, the city of Burlington, and the various people working for the courts and the law. One of the great advantages of researching a major historic murder case in a small town: because they don’t happen often, when they do, they’re big news. The local paper may add extra sheets to cover the details if the editor thinks he can make enough sales. As Sherwood Anderson wrote in his book, Winesburg, Ohio: A Group of Tales of Ohio Small Town Life, “The paper…had one policy. It strove to mention by name in each issue as many as possible of the inhabitants of the village.”

Let’s look at what this might mean for someone researching family history during a time period that coincides with the Florence Knoblock murder investigation.

Statements from possible witnesses

The Daily Republican included some early statements from various witnesses who might have seen a potential suspect. In addition to learning about what she saw, we learned that Mrs. E. E. Liggett worked at the Katy Store on West Neosho Street in Burlington and that she worked on Saturday mornings.

E. E. Liggett’s statement, from “Deacon Stevens Claims He Was in Independence at the Time of the Murder,” Daily Republican, June 2, 1925.

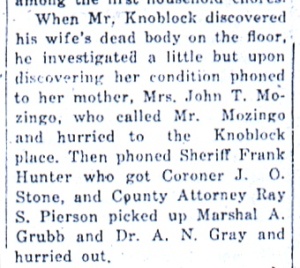

Law enforcement, medical personnel, and other officials

Sometimes when researching family members, we might find names and dates of major life events, but we don’t always know much about what those ancestors actually did for a living. Newspaper articles tell us the roles played by various official personnel. Imagine being able to understand exactly where your great-uncle-so-and-so was the afternoon of May 30, 1925. Here, we learn the names and roles of the sheriff, the coroner, the county attorney, the marshal, and a doctor.

From “Skull Crushed and Throat Cut–Mrs. Knoblock is Found by Her Husband Saturday Afternoon,” Daily Republican, June 1, 1925.

Possible suspects

Several different men are arrested during the investigation of the murder of Florence Knoblock. Because there was no apparent motive and no obvious suspects, anyone who was caught in the wrong place at the wrong time was likely to be arrested and questioned. For example, a man named Vance Fox cut through a farm field of William Strawn to shorten his walk home. After a manhunt involving a hundred people, he was taken into custody. A genealogist learned a lot about Vance Fox; where he lived, the fact that he was probably poor because he walked from Emporia to Strawn instead of taking the train or a car, and that he was healthy enough to make a 35-mile walk.

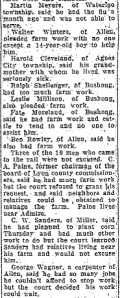

Subpoenaed witnesses

Both the Daily Republican and the Emporia Gazette printed lists of subpoenaed witnesses. In the case of State of Kansas v. John Knoblock, the number of witnesses would ultimately clear one hundred. Here is an excerpt from the list printed for the preliminary hearing. The genealogist will see names, family connections, and lots of people who lived in the same neighborhood.

Prospective jurors

My favorite newspaper articles involved the jury selection process. Reporters John Redmond and Bill White listed every juror and every excuse they used to try to get out of jury duty. The genealogist might learn where their relatives live and work. They might learn that their ancestor was hard of hearing or was recovering from the flu, or that they can’t afford the financial burden of sitting on a trial instead of earning a living.

A sampling of the juror selection process from the first trial. From “Making Good Progress Toward Securing Jury to Try John Knoblock,” January 12, 1926.

A sampling of prospective jurors from the second trial. From “Accept Two Jurors,” Emporia Gazette, May 6, 1926.

Reporting on other reporters

To emphasize how important the trial might be, reporters might take the time to mention other reporters and important citizens who are attending the trial as spectators. For example, John Redmond mentions a newspaper reporter and a magazine reporter present at the trial.

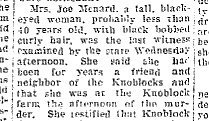

Trial witnesses

We expect to see information about testimony from witnesses in newspaper articles about murder trials. Genealogists may also learn details about the witness: where he/she works, lives, who he/she associates with, and even what he/she looks like. Although the local reporter might not go into great detail about local folks, an out-of-town reporter will make the extra effort to describe how witnesses appear on the witness stand. For example, here are two descriptions of Coffey County woman Stella Menard, a witness called by the prosecution, as written by Emporia Gazette reporter Bill White:

As I read through the newspaper articles about the Florence Knoblock murder, investigation and trials, I was overwhelmed by the hundreds of names that appeared connected just to this story. The tough part for the genealogist is learning about the major trials that might have happened in an area where his or her ancestors lived, and then accessing those newspapers if they’re not already available online.

As part of my research, I created a giant spreadsheet of all of the names I encountered in just the newspaper articles. Although they don’t all turn up in Shadow on the Hill, I wanted to make the information easily available for anyone who might be researching family who lived in Coffey County and Lyon County between 1925 and 1926. It’s also a handy way to keep track of the several hundred people who do turn up in Shadow on the Hill. As you explore the database, think not only of the trial, but what it was like to be on that witness stand, or hoping to avoid jury duty, or being interviewed by the paper for something you saw. It’s an enlightening way to think about your ancestors–as regular human beings experiencing a moment in time.