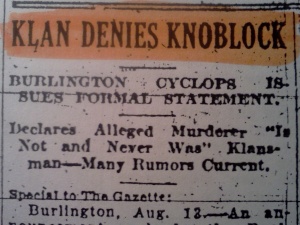

Shadow on the Hill readers know that bread dough played a role in narrowing down Florence Knoblock’s time of death.

Shards of broken dishes littered the hardwood. Bread dough, long past risen, had flowed over the lip of a crock, down the side of the stove, and onto the floor, where it began to dry out. A pan of washing water, likely pumped from the well that morning, sat on a chair.

We also know that bakery employees were able to testify to the time Florence Knoblock called to place an order for lard because they knew what stage the bread they were baking was in.

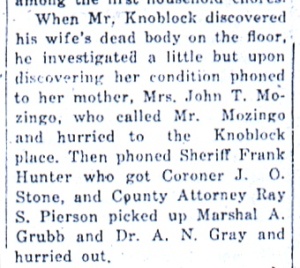

“I spoke with Florence on Decoration Day,” Ray said. “We were discussing compound and then she said, ‘John is coming to town and will talk to you.’”

“And at what time was this?”

“About nine o’clock,” Ray said. “I was sure it was nearly nine by the stage of the bread. It had been put in at seven and the dough was put on the bench just as she called.”

But for those of us who aren’t bakers, what does that really mean? Even though my mom was a superb baker, most of the things I make come out of a box. So I turned to someone who really knows her way around a kitchen: Veronica. Veronica not only bakes, but she wins RIBBONS at the Kansas State Fair (and not just the participation ones). Veronica is going to walk us through baking the old-fashioned way so that those of us who don’t bake from scratch can better understand how bread behaves and why it could be a valuable tool for determining how much time had passed since Florence’s death.

—

Hi, my name is Veronica and you can usually find me posting recipes over at my blog, Veronica’s Cornucopia. I like to eat (a lot), so I cook because I have to, but my true love and passion is baking. I’ve won many ribbons over the last several years at the Kansas State Fair for my cakes, cookies, quick breads, and yeast breads. Although, I have to admit, many of my yeast bread attempts (especially whole wheat) don’t turn out so well…

Since bread dough plays into the 1925 murder of Florence Knoblock, which Diana’s book, Shadow on the Hill details, she asked me if I would do a bread post for her readers. While I consider myself a yeast bread novice, I have made many loaves, some failures, and some successes, and I suppose I’m moderately suited for the task. In any case, I wasn’t going to turn down such an honor! Thanks, Diana!

The day Florence was discovered murdered in her kitchen, there was a kettle of over-risen bread dough on the oil stove that had escaped the crock and spilled down the side of the stove, and onto the floor. This was one factor that helped determine the timeline of the morning and her murder, by how much it had over-risen.

Now today if we need bread, most of us pick up a loaf while we’re doing our grocery shopping at the supermarket, but in 1925, bread wasn’t as easily available for purchase if you lived in the country. While Florence had placed an order for lard at the bakery, which her husband and son went to retrieve the same morning she was murdered, she did not place one for bread and had instead started some herself. Florence obviously was not a wasteful sort, and chose to do the things she had been raised doing, rather than paying a higher price for someone else to do it. Making the bread was just another daily chore that Florence had begun.

As tradition has it, each day of the week had it’s own assigned chore: Monday: Wash Day ~ Tuesday: Ironing Day ~ Wednesday: Sewing Day ~ Thursday: Market Day ~ Friday: Cleaning Day ~ Saturday: Baking Day ~ Sunday: Day of Rest. Florence was murdered on a Saturday so this might have been just the beginning of a long day of baking for her. Baking Saturdays would be my favorite chore day! Maybe it was Florence’s too, and she was in a haze of baking bliss before she met her maker. I’d like to think so.

I wanted to bake a loaf of bread in Florence’s memory, something that was old-fashioned and not fussy. I decided on this Grandmother Bread from Chickens in the Road. It’s an old, simple recipe that’s been in Suzanne’s family for generations, and while it doesn’t require you to harvest your own yeast the way Florence might have, it suited my purposes just fine. I’d like to think that Florence approves of me skipping a step made unnecessary by modern convenience, as I got the impression from the book that she was a no-nonsense kind of woman.

Grandmother Bread

Grandmother Bread

Printable recipe

Printable recipe with picture

1 1/2 cups warm water

1 teaspoon yeast

1/2 teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons sugar

3 1/2+ cups all-purpose flour

To start, you need to activate your yeast. I usually prefer to use rapid-acting yeast (bread machine yeast) because it’s easier and faster, but to get into the old-fashioned spirit to a degree, I stuck with active yeast. So sprinkle your yeast, sugar, and salt over warm water and let it rest so the yeast can get happy in it’s warm, sugary bath.

Or you could forget to add the sugar and salt like I did, and then add them along with your first cup of flour. See, it’s OK to mess up to a degree. If you’re new to bread making, it’s important to ask yourself, “What Would Florence Do?” Do you think she’d waste her precious yeast and start a new batch of dough because she forgot to add the sugar and salt at the right time? Heck to the no! She’d soldier on like a good early 20th century Kansas housewife. So will you.

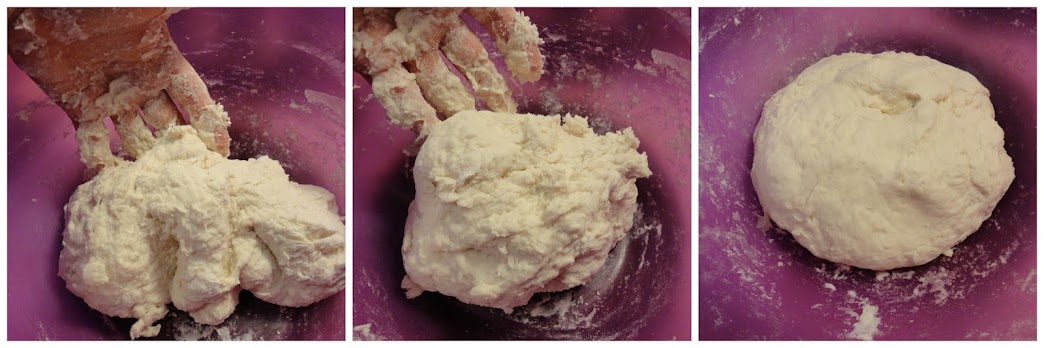

Mix that all up with your spoon and then gradually add the remaining flour, stirring as you go.

When it gets too thick to stir, flour your hands and start kneading more flour in until you get a smooth and elastic dough. Most people, including Florence, would flour a counter and knead it there because it’s efficient, but I went against my WWFD (What Would Florence Do?) theme and did what I usually do, kneading it in the bowl so I don’t have to clean up a bowl and a counter afterward. It’s aggravating and makes your neck and back sore, but hey. I’m all about less mess to clean up. Florence put off sweeping up her husband’s and son’s hair after cutting it that morning, so I’m thinking she’d be all about less clean-up.

Once the dough feels right (if this is your first time making bread, then knead flour in until it’s not very sticky, just very slightly tacky, and is nice and stretchy and elastic and smooth), oil your bowl and turn the dough over in it so that all sides are oiled.

Cover your bowl with a cloth (or plastic wrap if you’re not feeling the WWFD thing) and set it in a warm, draft free place. Florence chose to put it on top of her stove, which we know she had going and was warm since she was using it to boil a kettle of water for tea. My trick is to preheat my oven to 350F for one minute, then turn it off and put my bowl inside. Works great! Oh and sorry, Florence, please forgive my dirty oven that I’ve never cleaned. I don’t think you would have shirked that chore as long as I have.

Let it rest for an hour, or until doubled in size.

Most people, including Florence, would then place the dough on a floured counter and smooth it into a rectangle, then roll it up into a loaf, pinching the seams, and place it in an oiled bread tin. Again, I didn’t want to flour a counter and have to clean it up so I kinda just smooshed it together in my hands and then patted it down as evenly as I could in the pan. Florence is probably rolling over in her grave.

Cover the pan and let it rise until doubled, about 30 minutes or more depending on the temperature and humidity. I forgot about it and left it for an hour and you can see how much it had over-risen with only and extra half hour of rising. I imagine it really would have run out of the pan and down the sides like Florence’s dough if left unattended for hours on end.

But WWFD if she lost track of time and found her dough in this state? She’d smack that dough down and start over with the rise, that’s what! We ain’t gonna have no over-risen mushroom bread with big holes up in here. I had to go to our evening church service, so I put it in the fridge this time to slow down the rise. By the time I got back, about two hours later, it was perfectly risen–no shrooming over the sides.

But WWFD if she lost track of time and found her dough in this state? She’d smack that dough down and start over with the rise, that’s what! We ain’t gonna have no over-risen mushroom bread with big holes up in here. I had to go to our evening church service, so I put it in the fridge this time to slow down the rise. By the time I got back, about two hours later, it was perfectly risen–no shrooming over the sides.

Once risen, bake for 25-45 minutes at 350F. I found I needed to bake a lot longer than the recommended 25 minutes because I had to add soooo much flour to my dough (maybe the humidity, although the recipe does call for a lot of water IMO) so my dough was a little more bountiful that it probably should have been. Also, I was multi-tasking and toasting pecans for cookies at the same time. I’m sure efficient and no-nonsense Florence would approve.

Once risen, bake for 25-45 minutes at 350F. I found I needed to bake a lot longer than the recommended 25 minutes because I had to add soooo much flour to my dough (maybe the humidity, although the recipe does call for a lot of water IMO) so my dough was a little more bountiful that it probably should have been. Also, I was multi-tasking and toasting pecans for cookies at the same time. I’m sure efficient and no-nonsense Florence would approve.

Look at that gawjus loaf! You know it’s done when you take it out of the pan and it sounds hollow when you tap it on the bottom. I think I could have baked mine a little longer but it was still so, so good. If you under-bake your bread a bit, you can always toast the slices. That’s WFWD!

Now slather the top (and the sides and bottom) with butter while it’s still hot and try your best to wait until it’s cool to slice it. Oh who am I kidding? Well, wait at least fifteen minutes for best slicing. You’re probably thinking no-nonsense Florence wouldn’t be going hog wild with the butter so it’s time to ask, WWFD? Well, Florence’s family had cows, so I’m sure they had plenty of butter on hand, and despite her usual thrifty ways, according to me it was her secret pleasure to slather copious amounts of butter on freshly baked bread. So slather away! 😀

I want to thank Diana for writing this incredible true-life story of a Kansas murder, for all the hard work and research she put into it, and offering me some satisfaction in the long-time unsolved mystery. And for offering me this opportunity to be a part of her book in a small way as well! And thank you for reading. Now go get your bake day on! 😀

I want to thank Diana for writing this incredible true-life story of a Kansas murder, for all the hard work and research she put into it, and offering me some satisfaction in the long-time unsolved mystery. And for offering me this opportunity to be a part of her book in a small way as well! And thank you for reading. Now go get your bake day on! 😀

Recipe source: Chickens in the Road <–click the link for the two-loaf recipe