The history and current stories of the native and emigrant tribes of Kansas have been on my mind these past few days. My Sisters in Crime chapter (that would be a group of writers, not a group of criminals) was lucky enough to host tribal law expert Traci McClennan-Sorrell as our speaker this past weekend. And today, a story of a Wisconsin bill that would loosen the protection afforded to earth mounds constructed by indigenous people more than a thousand years ago–protection put in place after nearly 80 percent of these mounds were destroyed by farming and development–showed up in my Twitter feed.

The more I study Kansas history, the more I realize how little I know and understand the stories of the people who were here long before the rectangle that is Kansas came to be. Which is why during our Republic County research trip last May, Jim and I made a point of allowing time to visit the Pawnee Indian Museum, which is just north of Belleville and a short jog from the Nebraska border.

The Pawnee Indian Museum is Kansas’ first state historic site.

Here’s the first thing to know about the Pawnee Indian Museum: The land was not originally preserved because it tells the story of an amazing group of people who lived in Kansas hundreds of years ago. Landowners George and Elizabeth Johnson deeded it to the state of Kansas in 1899 (which accepted it in 1901, making it the first state historic site) because of the mistaken believe that explorer Zebulon Pike (of Pike’s Peak fame) stopped here in 1806 to raise the American flag west of the Mississippi River for the first time. And while he did stop in a Pawnee village to do so, it turns out that he was actually in the Pawnee village 40 MILES NORTH of the state historic site in the village the Pawnee moved TO after abandoning the one that was preserved.

However, this error in geography probably went a long way to protecting the Republic County site from being plowed into oblivion. The result is a truly wonderful site dedicated to sharing the story of the Pawnee in the late 1700s.

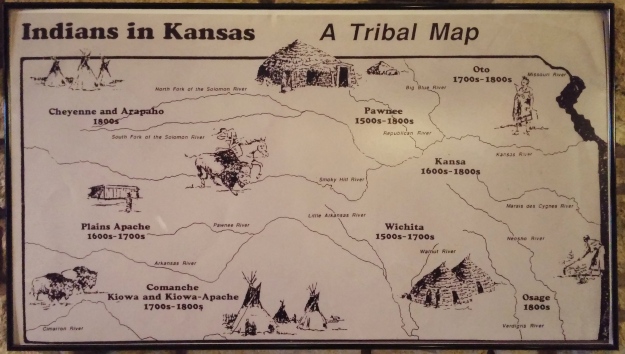

A map of the earliest tribes to live in the area now called Kansas.

In this area by the Republican River, a band of Kitkehahki Pawnee built an entire village of earth lodges, which were surrounded by a fortification wall. After the village was abandoned, the earth lodges, which were built over carefully packed depressions, settled in place, complete with any remaining contents. Part of the fortification wall still exists. A handful of the depressions have been excavated. In 1967, the museum was built over the largest unexcavated depression in the shape of a Pawnee earth lodge, and archaeologists carefully unearthed the contents, exposing them but leaving them in place.

A model of what the Pawnee lodge would have looked like when it was still in use.

As a result, when you enter the Pawnee Indian Museum, you don’t feel like you’ve entered a museum. You feel like you’ve entered a Pawnee earth lodge. Wooden posts that once held up the roof fell in place. Grains, shells, pottery, and other tools lay exactly where they were found. The storage pit–which is several feet deep (the Pawnee buried their supplies underground, hiding them from anyone poking around their village during the seasons they were elsewhere)–is visible. And then there is the faint scent of wood smoke, which will make you feel like the inhabitants could return at any moment.

A view of the excavated area in the Pawnee Indian Museum.

The Pawnee did not live in the village all year long. During the hunting seasons, they followed herds of bison. The women also cultivated crops and stored them in the storage pits.

Earth lodge storage pits were very deep.

A sacred bundle–a bundle of items important religiously and symbolically to a Pawnee family–is reverently displayed over the sacred area of the earth lodge. It is the only artifact that cannot be photographed.

Around the perimeter of the excavated area are several displays about the history of the Pawnee. Audio recordings of memories, journals, and the Pawnee language make the visit to this site even more meaningful.

The museum does not end in the building. The site includes numerous depressions, and a walking trail and signage help you interpret the depressions and remaining fortification walls.

Signs along the walking trail help you interpret the depressions and remaining fortification walls.

After centuries on the Plains, the Pawnee’s population began to decline. As other tribes were pushed into the area that would become Kansas, the Pawnee were pushed out, and the tribal members who were not killed off by disease ultimately ended up in Oklahoma. By 1900, only about 600 Pawnee remained.

According to one of the displays at the Pawnee Indian Museum, Pawnee populations declined rapidly in the 1800s.

If you visit the Pawnee Indian Museum, give yourself several hours to explore the museum, listen to the audio clips, and wander the grounds. It’s also a great museum for asking questions. Museum site manager Richard Gould has been researching the history of the Pawnee for years, and his insight made our visit even more meaningful.

This site does an amazing job of making the story of the Pawnee accessible to visitors regardless of what knowledge they may have of the history of native tribes. I highly recommend making the time to visit this museum.

We are guardians of all that exists. I hope that we do a better job going forward.

Where would the Comanches have come from before 1700? By the time they were rendered ineffective in the mid- to late 1800s, they would have had a lot of European blood mixed in.

According to the information available from the Kansas State Historical Society, the Comanche originated in Wyoming and Nebraska, headed to New Mexico, where they obtained horses from the Spanish, then made their way east into Colorado, then the western parts of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Thank you!

Thanks for the nice article about a great museum. Unfortunately, it’s off the beaten path so doesn’t get the number of visitors it deserves (please note that it is not North of Belleville, but West). Richard is an amazing man who not only manages the facility, but he has lived on the premises as curator for over 25 years. I would not doubt if he is the leading expert on the Pawnee of this region. He’s happy to address any questions guests have.

For readers who may not know, there is a bison farm which welcomes visitors nearby the Pawnee Museum.

Thanks so much for your comments, Kansas Pete! You’re right, I just mapped the route from Belleville to the museum and it’s definitely northwest. I’ll update the page.

The museum itself does a great job telling the story of the Pawnee, but being able to ask Richard questions made it an extraordinary visit. We learned so much about the people and the history of the land.

Thanks for mentioning the bison farm! I expect to make another trip out to Republic County; we’ll have to add it to our list of places to explore.

This is a really cool place. I was there and so enjpoyed it.

That photo of the population stats just knocked my socks off. I’d known the population dropped of course, but seeing those stats really brought it home.

Isn’t it astonishing? Next to it, there was a display that listed the names of the remaining Pawnee in 1903, and after walking through the museum and getting to know who these people were and how they lived, it breaks your heart to get to that panel.

Sounds like a fascinating place. I just started reading a fictional story that features a Pawnee, so this was interesting additional background. I had heard of the tribal name before, but had no idea they built earthen dwellings like this. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks for posting! What book are you reading?

That sounds like a wonderful museum. Is your chapter of Sister-in-Crime related to the one in St. Charles County, Missouri? I am not a member, but have been a frequent visitor. It’s a really great group.

There is a chapter in the St. Louis area. If that’s the one you mean, then it’s part of the same national organization! Our group brings some great speakers. I learn a lot.